Dengue could spread to areas already affected by the presence of invasive Aedes mosquitoes, but still hardly affected by the disease.

The rapid spread of dengue, a viral disease transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, represents a global pandemic threat. The risk of transmission is increasing due to globalisation, through travellers carrying the virus easily and the rapid spread of mosquito vectors. For this reason, it is necessary to assess and predict the geographical extent of dengue spread by predicting geographical changes in the risk of transmission. In addition, there are factors whose involvement in dengue transmission may be underestimated, such as the contribution of the sylvatic cycle (i.e., transmission by sylvatic vectors between primates, including humans).

The journal PloS Neglected Tropical Diseases has recently published an article entitled “Worldwide dynamic biogeography of zoonotic and anthroponotic dengue”, which analyses, with high-resolution global maps and the most up-to-date database of dengue cases available, the geographical changes in the risk of dengue transmission since the end of the 20th century. This study was carried out by the group of research on Biogeography, Diversity and Conservation, in the Department of Animal Biology of the University of Malaga, in collaboration with the International Vaccination Centre of Malaga (Ministry of Health) and the Centre for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

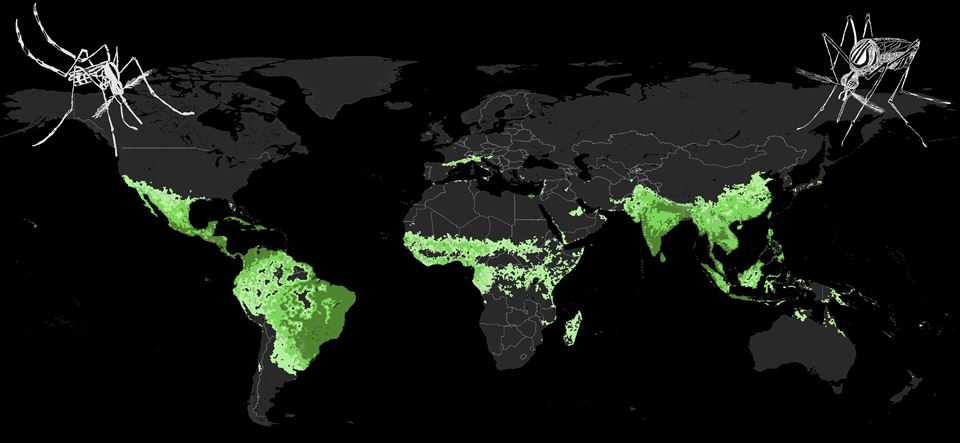

The results of this research consider three possible biogeographical scenarios linked to the risk of dengue transmission: (1) Areas with favourable conditions for both the presence of the virus and mosquito vectors, favouring the risk of transmission. This was evident in South Asia, where areas that were dengue-free two decades ago, such as Pakistan, became environmentally favourable for the presence of dengue and vectors. Our models for the 20th century predicted this change in the risk of transmission, which was validated by the 21st-century epidemiological reports. In regions with this type of scenario, health entities should ensure close microbiological and epidemiological surveillance. (2) Areas with environmentally favourable conditions for the presence of the virus, but not for mosquito vectors. This scenario became evident in South America in large regions of the Amazon basin at the end of the 20th century. However, by the 21st century, they also presented favourable areas for mosquito vectors, allowing transmission to be favoured. The rapid human-influenced dispersal of Aedes and their adaptive potential mean that the environment they currently inhabit does not represent the complete range of ideal conditions for the establishment of new populations. Therefore, the areas currently free from vectors where the environment is, however, favourable to their presence, should be taken seriously in order to prevent the arrival of invasive mosquitoes. Finally, (3) Environmentally favourable areas for the presence of mosquito vectors, but not for the presence of the virus. This is the case, for example, in southern Europe. In Spain, the tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) began to establish itself successfully in the early years of the 21st century. Although the region is far from the dengue endemic area, travellers frequently arrive with the disease. In 2018, some autochthonous cases were reported for the first time in Andalusia, Murcia and Catalonia. In this case, if the arrival of the virus is not efficiently controlled, there is a risk of transmission due to the presence of the tiger mosquito. Health entities should consider raising public awareness in order to help control the tiger mosquito.

The article published in PloS Neglected Tropical Diseases also considered the contribution of primates and forest mosquito vectors in increasing the risk of dengue transmission in parts of Asia, Africa and South America. The contribution of primates represents a small percentage, yet is documented in Asia and Africa. In the Americas, direct zoonotic transmission has not been detected, although this study provides biogeographic evidence of this type of transmission in the Amazon basin and in the Atlantic forests of southern Brazil, where zoonotic transmission of yellow fever (with which dengue shares mosquito vectors) is known. Areas of zoonotic transmission may be increasing in Africa, the Americas or Asia, perhaps as a consequence of deforestation, climate change and the geographical spread of vectors.

Globally, the maps show areas already exposed to the presence of invasive Aedes mosquitoes, but hardly yet affected by dengue (e.g., China, Papua New Guinea, northern Australia, southern United States, inland regions of Colombia and Venezuela, Madagascar, and southern Europe and Japan), which have the potential to experience a spread of the disease. This research contributes to the development of different prevention strategies by taking into account the spatial distribution of different factors that favour the risk of dengue transmission around the world.

Funding: Project CGL2016-76747-R of the Spanish Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad; FEDER funds; FPU 16/06710 grant of the Spanish Ministry of Education

Link to this news in the UMA website: https://www.uma.es/sala-de-prensa/noticias/investigadores-de-la-uma-advierten-del-aumento-del-area-de-distribucion-de-los-mosquitos-vectores-del-dengue/

Interview: https://www.gideononline.com/2021/07/07/tracking-dengue-an-interview-with-alisa-aliaga-samanez/

Blogs: https://forestsnews.cifor.org/74205/how-deforestation-poses-dengue-pandemic-risk-for-africa-and-asia?fnl=enen; https://www.gideononline.com/2021/07/28/new-dengue-study-identifies-new-high-risk-countries/

Link to the whole article in PloS Neglected Tropical Diseases: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009496

Repercusion in the press: La Opinión, Europa Press, 20 Minutos, Telecinco, Teleprensa, Novaciencia, Gente Digital